Last week my wife and I took a brief trip into U.S. history. My wife had always had the dream of visiting the White House and the Capitol building. We’re both U.S. citizens, but she immigrated from Vietnam 33 years ago, and I was born here and can trace my ancestors back to the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1634. We’ve traveled the world, but neither of us has visited the political and historical sites in our own country. Feeling as safe as we’d ever be from COVID because of our 2nd Moderna boosters, we decided that now was the time to visit Washington, DC and Philadelphia. We saw the White House, toured the Capitol Building, visited Independence Hall, saw the Liberty Bell, and toured Betsy Ross’ house. We listened to tour guides, read brochures, and even I, born and raised in the U.S., felt as if I was learning something. It’s a trip I wish every U.S. citizen could make.

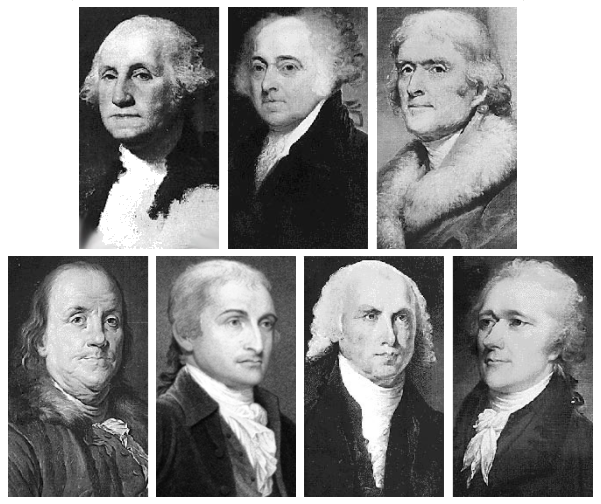

Declaring independence from Britain, which at the time, was probably the most powerful nation in the world, took great courage. The signers of the Declaration of Independence were committing treason in the eyes of King George III and could have been hung. Forging the constitution of the United States was less life-threatening, but more ground-breaking. The British had their Magna Carta, but their constitution is an unwritten one. To put on paper the basic structure and procedures of a free government was both audacious and brilliantly intelligent. Between them, the framers of the two documents may have represented a perfect storm of intellect and vision. In terms of politics, Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, Madison, Hamilton, Jay, Adams, and several others were as unique as the physicists, Einstein, Fermi, Bohr, Planck, Heisenberg, and their colleagues in the early 20th century. Like the work of the physicists, what the American founders created was a model of clear thinking, brilliant reasoning, practical application, yet limited by the state of civilization and thinking of the time. Similar to the physicists, the framers knew they hadn’t solved all the puzzles and that their work would need to be modified in the future. They were bold, but humble. The job of describing a workable, democratic government is too large for it to be captured at any one time by any one group of people. But they made marvelous progress–in spite of serious errors and omissions.

The U.S. constitution is elegant in its brevity and simplicity. The ideas are profound: balancing central leadership and authority with representative government and the supremacy of law, covering everything from term limits to qualifications to run for office, to impeachment, to raising money and armies, to electing representatives. But not everything was included. Slavery was an issue that was kicked down the road, and untouchable in the near term. Women’s rights were not even considered. In fact, preserving the rights of individuals against the majority and the government, was not guaranteed in the original document, an omission that led to some, such as George Mason, refusing to sign it. These rights were included as amendments four years later in the Bill of Rights. The big issue dividing those that would later become Federalists or Democratic-Republicans, was how much power to allot the central government vs the individual states. It’s an issue that is still not settled.

What really grabbed my attention were statements by opponents such as Hamilton and Madison, that they disagreed with some of the major points in the constitution but still promoted its passage because compromise was superior to holding out for one’s opinion at the risk of jeopardizing the entire project. In fact, no two men could hardly disagree more than Hamilton and Madison, yet they jointly wrote what are now known as the Federalist Papers to convince people to ratify a constitution both felt was deeply flawed, but good enough around which to fashion a workable government. Hamilton’s conclusion was that what they ended up with was, “better than nothing.”

Every American should listen to the speeches from that time or read at least a few of the Federalist Papers. People in the late 1700’s did not talk in sound bites. They expounded at length and in language that is challenging for even a well-educated person of the 21st century to fully understand. The writers were intelligent, well-read, literate, and dedicated to using their intelligence and their reason, rather than rhetoric and trigger-words. They never spoke to the lowest common denominator or dumbed down their arguments to latch onto their readers’ emotions. These were smart, sincere men who thought deeply about what they were doing and put the good of the new nation ahead of their personal agendas.

As we toured and listened, in Washington and Philadelphia, the congressional hearings on January 6th were going on inside the House of Representatives. I wondered how many of those who blithely invaded our Capitol building, demanded that the Vice President, in violation of the constitution, alter the results of the Electoral College, trashed the building, and went hunting for politicians they hated, would have acted in such a way if they had studied how deliberately and carefully our laws and procedures came into being. Everything they did violated the spirit of the Founding Fathers, yet they claimed they were standing up for the constitution, a document dedicated to establishing orderly rules rather than mob rule as the mechanism of government.

Neither as a group nor as individuals were the constitutional framers infallible. They were prescient in some ways and myopic in others, products of their times, brilliant, but still products of their times. Those were times when the slave business was profitable, rampant, and unquestioned in much of the country. They were times when women had almost no rights in terms of voting or owning property or businesses. They were times when owning a gun was necessary for joining the state militia and protecting the new country against outside threats and internal rebellion. Memories of government intrusion were still ripe after years under British rule. The constitution they created, including its Bill of Rights, reflected the biases and attitudes of those times. It is not a document that deserves to remain unchanged for the ages. The framers knew this, although they had no idea how times would change in the decades to come.

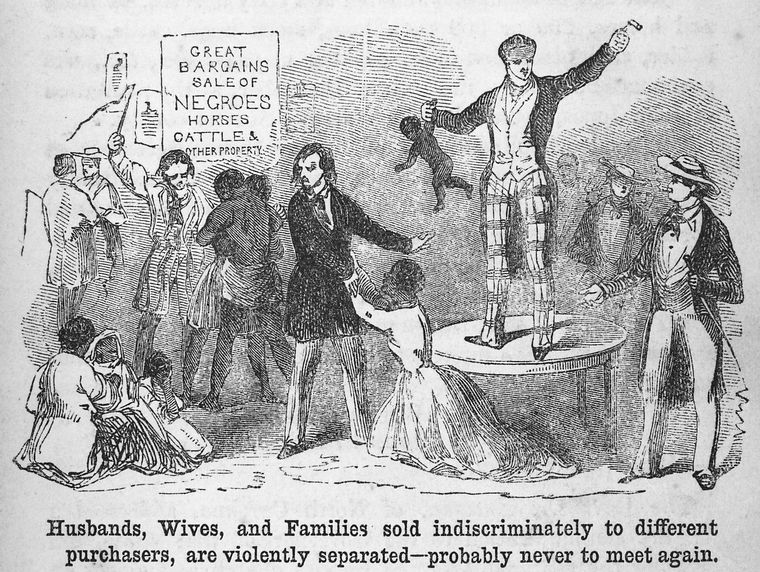

It was also Juneteenth and we witnessed celebrations in both Washington and Philadelphia. We toured the exhibit of Afro-Atlantic heritage at the National Galleries of Art and saw depictions of slave ships, slave auctions, and slave whippings. The founders weren’t perfect, and not completely courageous. They never mentioned slavery, but instead referred to “imported persons.” They expressly protected such “importation” for the next ten years and even allowed a tax (“not to exceed $10”) on each person imported. Twenty of the thirty-nine signers of the constitution were slave owners. Their unwillingness to address slavery left an open wound in the country that festered for another seventy-five years before finally bursting open and splitting the country apart. The continuation of slavery was not even a main sticking point for most of the signers.

Forming our nation was a monumental achievement. It was meant to throw off the chains of oppression from Britain, and it did so, but left other chains intact—chains on women, African Americans, and Native Americans to name some, but not all. It outlined how democracy could work, and later did work to reverse some of the oppression for these groups. It established separation of religion and the government and protected religious freedom. It did so without referring to any religion, neither to God nor to Christianity, which was the religion of the majority of the people. Several of the most prominent founders, such as Jefferson, Franklin, Washington, Madison, and others, were Deists, subscribing to a belief in a vague higher power but not a supernatural God who intervenes to reward or punish humans or who performs miraculous acts on behalf of his worshippers. Thomas Jefferson famously re-wrote the first four books of the Bible’s New Testament, leaving out the virgin birth, the miracles, and Jesus’ resurrection and ascension to heaven after death, all of which he considered myths. Thomas Paine, whose pamphlet “Common Sense,” was instrumental in garnering support for independence, was a vocal Deist, and was accused of being an atheist. His ideas affected all of the founders. The idea that the constitution embraces a “Judeo-Christian” belief system is patently false and is the source of a lot of mischief by those who cannot separate their religious views from their political ones. Nevertheless, independence was won, a constitution was written, slavery was eventually prohibited and abolished, women were finally allowed to vote, and we struggle on, following and sometimes modifying the incredible document and continuing a heritage that we, as Americans, have been given by a very special group of men over two-hundred years ago. It’s an inspiring story.

Casey Dorman is the author of the scifi thriller, Ezekiel’s Brain. Buy it on Amazon.

Subscribe to Casey Dorman’s Newsletter. Click HERE

Casey, I’m wishing for you both that your visit into our history could be more than you call brief. I’ve loved every trip to DC and actually all up and down the historical East Coast. Every trip is so full of new and fascinating exhibits and knowledge. Go again and again. … Bunni B

Thanks, Bunni: I agree. I lived in Boston for 14 years and saw the historic sites there ( had an office a block away from a building that had a plaque on it saying that it was where the patriots plotted the Boston Tea Party!). I’ve been to Washington a fair amount but not to visit the historic and government sites. First time in Philadelphia. It was both inspiring and educational