Life on a Tidally Locked Planet

Habitable planets are a staple of science fiction, but until the mid-1990’s, no planets inside of what is referred to as the habitable zone—a zone around a star in which a rocky planet could support liquid water—were known to exist. Then, beginning in 1996 with the discovery of the planet, 70 Virginis b, a number of habitable planets and satellites of gaseous planets were discovered, leading to the assumption that our galaxy may have numerous planets and moons that could sustain life. Most of the search for planets inside the so-called “Goldilocks Zone,” where the surface of the planet is neither too hot nor too cold for liquid water and life to exist, has aimed at finding earth-size planets orbiting Solar-like stars at distances similar to our own planet.

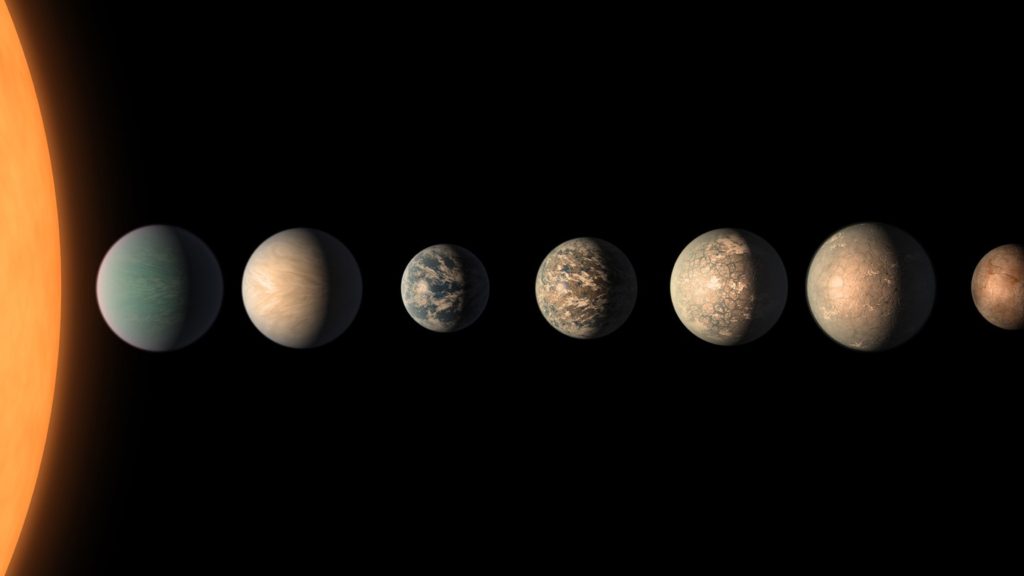

Recently, led by Belgian astronomer Michaël Gillon, researchers have begun to focus on a different set of stars and the planets that orbit them. Gillon’s team, using a pair of robotic telescopes in Chile and Morocco, but controlled in Belgium, named Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope, whose acronym, TRAPPIST, has an appropriate association with Belgium (although the Trappist Order of monks originated in France), and, for some of us, beer (Trappist monks are famous for their Belgian beer), focused on ultracool dwarf stars as part of a survey called SPECULOOS (Search for habitable Planets Eclipsing Ultra-Cool Stars). In 2015, they discovered an ultra-cool dwarf star they named TRAPPIST-1, and which ultimately was revealed to have 7 earth-size planets orbiting it, all of which are within the habitable zone, although the three closest to the star may either be too hot for liquid water or too small to retain an atmosphere (in the case of Trappist-1d) and the one farthest away too cold, leaving three planets with a good probability of both liquid water and the ability to support life.

Ultra-cool dwarf stars, as their name suggests, are small and give off much less light than our sun. There are many of them, in fact three-quarters of the stars in our galaxy may be ultra-cool dwarfs. With TRAPPIST-1, its 7 orbiting planets are all closer to the star than Mercury is to our sun, which is why some of them may have liquid water and habitable temperatures and at least one would have the same illumination as earth does from our sun. Being that close to their star, TRAPPIST-1’s gravity affects planetary rotation so that all 7 are probably tidally locked, meaning that the period of their rotation matches the period of their orbit, and they always have the same side facing the star and the other side perpetually dark, as our moon is with regard to earth.

Living on a planet that is tidally locked presents challenges. Depending upon the thickness of the atmosphere and air and sea currents, the temperature on the two sides of the planet could be similar or wildly different. At the extreme, temperature differences between the two faces of the planet could be so great that one side is a hot desert or boiling ocean and the other a frozen tundra or ice. A narrow temperate zone could support life near the “terminator line” dividing light from dark sides. If life existed, it would have no circadian rhythms as we have on earth.

Nebula award-winning author, Charlie Jane Anders has captured the difficulties of living on a tidally locked planet in her novel, The City in the Middle of the Night, a Hugo award finalist. Most of the inhabitants of January, the planet, are descendants of settlers from earth, who arrived in a “mothership,” which still orbits the planet, although it was long-since abandoned. They live in two cities, both within the terminator zone, the twilight zone between the light and dark sides of the planet but are separated by a desert and the “Sea of Murder.” They are not alone on the planet. Giant carnivorous octopi live beneath the surface of the ocean and deadly oversized “bison” that feed on people live on the “night” side. Also on the night side are giant “crocodiles,” which have large hind legs and small forelegs, a giant pincer where a head might be, and smaller, soft tentacles. They are both feared and eaten as food by the humans.

While The City in the Middle of the Night presents a story that is dominated by the conditions of the planet, it is a very human story, told from the points of view of two characters. One of them, “Mouth,” is a rough and dangerous female smuggler who transits between the two cities, Argelan and Xiosphant, where, in the latter, because of the never-changing orientation of the city to light from its star, there is an obsession with time in a desperate attempt to restore circadian rhythms by shuttering everything in the city each “night” and keeping everything on schedule throughout the “day.” Argelan has no such obsession, although it is also in the terminator zone. Its people are less orderly, less serious and more focused on living for the here and now. The other character, and in some ways the heart of the story, is “Sophie,” a young woman who is closely attached to her charismatic friend, Bianca, and only gradually discovers of the depth of her love for her. Sophie is thrust out of the city into the night side of the planet and learns that the fearsome crocodiles are intelligent, telepathic, and empathic creatures who are struggling to keep their race and their complex and advanced city alive in the face of the planet’s harshness and the encroachment of humans.

The City in the Middle of the Night is everything a great science fiction novel should be, with elements reminiscent of Ursula LeGuin’s The Left Hand of Darkness, and some similarities to Stanislaw Lem’s favorite theme of the difficulty comprehending alien intelligence. It is also a coming of age novel, particularly in Sophie’s story, and a fantastical, but reality-based exploration of what life could be like on a tidally locked planet. I discovered it as I was doing research for my own books, Ezekiel’s Brain (forthcoming, NewLink Publishing) and its sequel, Prime Directive, the former in which parts of the novel take place on tidally locked planets orbiting Proxima Centauri, Ross 128, and Groombridge 34, and the latter, which is still being written, in which much of the novel takes place on TRAPPIST-1 planets 1-d and 1-e.

A link to The City in the Middle of the Night on Amazon is here. I highly recommend it.

Comments or questions? You can reach Casey Dorman by email at [email protected]

Share this newsletter with friends. Use the email, Facebook or Twitter links at the top of this page.

If you’re not already on our mailing list and want to be, subscribe to Casey Dorman’s newsletter by clicking SUBSCRIBE.