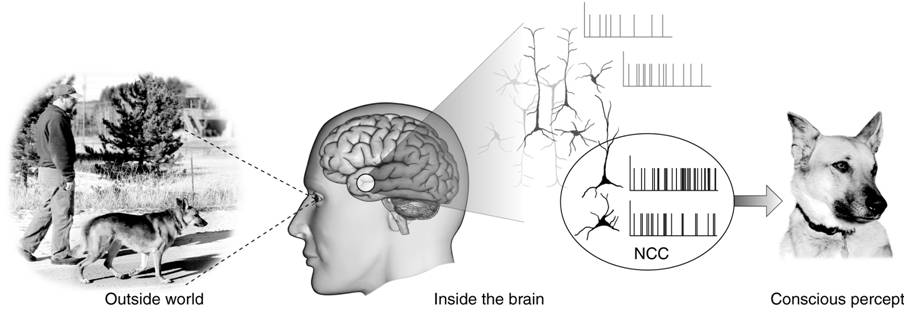

Is Consciousness an Epiphenomenon? Image from Christof Koch () “Figure 1.1: Neuronal correlates of consciousness” in The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach, Englewood: Roberts & Company Publishers, p. 16 ISBN: 0974707708.

Image from Christof Koch () “Figure 1.1: Neuronal correlates of consciousness” in The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach, Englewood: Roberts & Company Publishers, p. 16 ISBN: 0974707708.

If the question or some of the words in the title are unfamiliar to you, it means: could consciousness be something that exists, but is simply a by-product of brain activity with no actual impact on how we behave? In other words, our brain activities produce our behavior, and we’re aware of some of what goes on in those brain activities, but our awareness doesn’t impact how we behave.

But of course, we know why we do things. Don’t we? Don’t we make conscious decisions and then behave according to them? If the answer to the question in the title is no, then we only think we know why we do things and we only think we behave according to our conscious decisions. Such a suggestion sounds obviously wrong. It doesn’t square with our experiences. Yet this is exactly what some psychologists, neuroscientists and philosophers are now saying. They are in a minority, but I think their arguments are worth considering.

Why does the answer to the question matter? For many people, if our conscious decisions don’t cause our behavior, what happens to the concept of free will? It turns out that the answer to that question is almost as difficult to arrive at as the question of whether consciousness has an effect on behavior, so I will postpone that discussion. For my part, I want to know the answer because I am  curious about the human mind, and because I write books about AIs, robots, and androids and I have to deal with the issue of whether machines can be conscious. If consciousness doesn’t affect humans’ behavior, perhaps it isn’t an important question to ask about machines.

curious about the human mind, and because I write books about AIs, robots, and androids and I have to deal with the issue of whether machines can be conscious. If consciousness doesn’t affect humans’ behavior, perhaps it isn’t an important question to ask about machines.

Some serious psychologists, neuroscientists and philosophers (e.g., Halligan and Oakley, 2021) have come to the conclusion that our consciousness is an epiphenomenon and has no effect on what we do. Their reasons are related to the large variety of things we have learned can be done without being aware that we are doing them. This is most striking under hypnosis, but can also happen simply through suggestion and as a result of some brain lesions. In addition, there are several examples of people being aware of doing things that are not happening (e.g. wiggling one’s ears, moving a phantom limb). Probably more importantly, we generally are unable to describe how we do many everyday cognitive activities, e.g. name a familiar object, do simple addition or multiplication, even read. Many of these activities were done slowly and deliberately when we were learning them, but once they were learned, they occur automatically, whether we want them to or not. Try not to know what 2+ 2 equals or try not to read the following word: the. Is that just pure memory or is our mind calculating and we are not aware of it? Try not to read the following nonsense word: smat. Try not to calculate 95+5. You probably didn’t memorize either of those answers, but your brain computed them automatically and your conscious mind is unable to stop it from doing so.

A persuasive piece of evidence for some people is an experiment by Libet et al in 1983 in which subjects made a spontaneous movement while gazing at a clock and reported to the experimenters when they “decided” to make the movement. Although the decisions preceded the movements, EEG leads attached to the subjects’ heads indicated that a readiness potential in the brain preceded the decision by several hundred milliseconds. Libet interpreted his findings to mean that conscious decision making did not cause the brain to initiate the movement. Libet’s experiment has been interpreted to mean that free will is an illusion, but Libet didn’t go that far and neither will I. Assuming it’s a valid demonstration of what he said it is, it shows that, in some instances, the model of consciousness causing behavior is incorrect. Consciousness appears to be a report of decisions our brains have already made.

Assuming that consciousness plays no part in causing our behavior, what is its value? Halligan and Oakley describe consciousness as a “personal narrative,” which broadcasts the outputs from non-conscious brain systems “that have access to cognitive processing, sensory information, and motor control.” Why would such a system evolve if it was of no use to us? Halligan and Oakley believe that the advantage of the personal narrative system is to provide information on our thought processes to others who can then understand and predict our behavior and to us who can, by analogy, predict others’ behavior as well as use the memory of our conscious thoughts as at least a partial account of cognition that we can copy in new, similar situations or pass on to others, including future generations.

Would there be an advantage to having an AI be conscious? This is something I consider in my book, Ezekiel’s Brain. There certainly would be an advantage to humans who were trying to monitor an AI if the AI gave a running account of what it was thinking and doing, even if such accounts were, so to  speak, after the fact. If it were isolated, there would be little use for an AI to be aware of the outputs of its cognitive processes since it could use those outputs without being aware of them. If, as in Ezekiel’s Brain, a community of AIs lived together, there would be a similar advantage to that for humans. Understanding and predicting others’ behavior would be enhanced, and acquired skills could be passed on to others, including future generations.

speak, after the fact. If it were isolated, there would be little use for an AI to be aware of the outputs of its cognitive processes since it could use those outputs without being aware of them. If, as in Ezekiel’s Brain, a community of AIs lived together, there would be a similar advantage to that for humans. Understanding and predicting others’ behavior would be enhanced, and acquired skills could be passed on to others, including future generations.

Philosopher Susan Schneider, in her book Artificial You, says that we cannot be certain that an intelligent alien species would be conscious. She also thinks that any alien that visits us on earth will likely be a machine, either because that’s the species that is advanced enough to send a visitor to us, or because only a machine can live long enough to move from star system to star system, even if they are only a representative of an organic species that built them. She sees no reason that such a machine would be conscious.

That consciousness has no power to cause behavior is a counter-intuitive idea and violates most people’s view of how our minds and bodies work. However, it’s not outside the realm of possibility and should give all of us—not just science fiction writers—food for thought.

For an extended discussion of this topic, including how epiphenomenalism applies to complex cognitive processes, see Dorman, Casey. Is consciousness an Epiphenomenon: Extended Discussion. https://caseydorman.com/is-consciousness-an-epiphenomenon-extended-discussion/

References:

Halligan, P. W., & Oakley, D. A. (2021). Giving Up on Consciousness as the Ghost in the Machine. Frontiers in psychology, 12, 571460. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.571460

Libet, B., Gleason, C. A., Wright, E. W., & Pearl, D. K. (1983). Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activities (readiness-potential): The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain, 106, 623–642.

Schneider, S. (2019). Artificial You: AI and the Future of Your Mind. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Ezekiel’s Brain may be purchased through Amazon by clicking HERE.

Want to subscribe to Casey Dorman’s fan newsletter? Click HERE.