John Searle’s Chinese Room (1) thought experiment is often used as an argument for why AI is not, and perhaps cannot be, conscious. The Chinese Room is a hypothetical room in which a non-Chinese-speaking person sits with access to a source (a box of note cards, a book, a list) that provides Chinese answers to Chinese language questions that are passed into the room. The person in the room takes a message, looks it up in his source, types the indicated response, then passes it back out of the room.

From the outside, it appears as though the person in the room understands Chinese, but in fact they don’t. They only know how to respond with Chinese phrases they looked up when presented with a Chinese question. Similarly, it is argued, a computer or AI is like the Chinese Room. It simply looks up responses to inputs and provides them as outputs without understanding either the input or output.

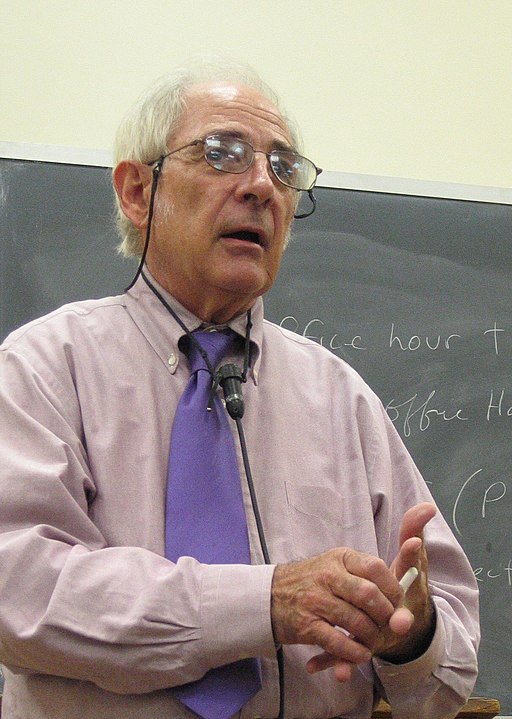

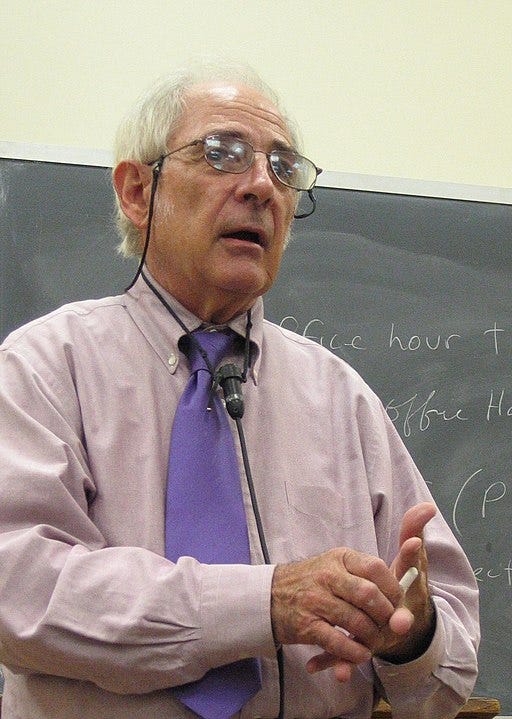

Searles’ original proposal has generated literally thousands of commentaries and is generally taken to be an attempt to refute the idea that a computer or AI understands the meaning of the symbols it takes as input or produces as output. Searles identifies this with a lack of consciousness, which he says has semantic content. He regarded it also as a refutation of the validity of the Turing Test, since the Chinese Room, if it were a computer, would convince a human that it was conversing with a human who understood Chinese, but that would not be so.

Several commentators have likened ChatGPT to the Chinese Room, claiming that it has no understanding of the words it takes as input or produces as output, although it gives the impression that it does.

Is ChatGPT a real-life instance of the Chinese Room, as some have claimed? Technically, the AI is not like the person in the room because it doesn’t have a library of words or phrases it looks up to match to the message coming into the room. An LLM, such as ChatGPT, has layers of neuron-like nodes with connections between layers and weights assigned to connections that determine if the nodes “fire,” which means that they pass activation forward to the next layer. Words are represented by tokens that include words, subwords (e.g., syllables), sometimes word pairs, punctuation, mathematical operation signs, etc. All of these work together to raise or lower the probability of a word being generated as a response. It’s transformer architecture lets it take into account a wide breadth of text for context to feed into the decision. The basic neural net architecture was originally developed as trainable artificial neural networks that were meant to represent a simplified model of how the brain operates. Its information is “stored,” so to speak, in the connections and weights, that determine how the system works, not in look-up files, as in the Chinese Room.

It’s important to realize that many of the early developers of neural networks, such as Warren McCulloch, Frank Rosenblatt, David Rummelhart, and James McClelland, were neuroscientists or psychologists, not computer engineers, and their aim was to understand how a brain that was filled with connected neurons might operate.

The inner workings of ChatGPT aside, what would allow us to determine whether it “understands” its input or its output? What if it could paraphrase a sentence using entirely different words? What if it could describe how a person hearing the sentence would behave and how they would behave differently if they heard a slightly different rendering of the sentence altering one or two key words? Or what if it could describe how two people with different backgrounds might respond differently to the meaning of the same sentence (e.g., a river fisherman instructed to “meet me at the bank” vs a bank teller instructed to “meet me at the bank”)?

I asked ChatGPT 3.5 to respond to the last question. The transcript is below.

Me:

Two men, Bob, a river fisherman, and Jim, a bank teller, are both told by a third person, Ralph, to “meet me at the bank.” Where will each of them go to meet Ralph?

ChatGPT:

Based on the information provided:

1. Bob, the river fisherman, will likely interpret “the bank” as referring to the bank of the river where he fishes. So, he will go to the riverbank to meet Ralph.

2. Jim, the bank teller, will likely interpret “the bank” as referring to a financial institution (like a bank building). So, he will go to an actual bank building to meet Ralph.

So, Bob will go to the riverbank, and Jim will go to a bank building to meet Ralph. The confusion arises from the different interpretations of the word “bank” based on their respective backgrounds and experiences.

ChatGPT’s answer is impressive and seems to indicate that it understands both the dual meanings of “bank” and that different people’s perspectives could lead them to interpret the meaning of the word differently. Searle might reply that ChatGPT produced its response based on probabilistic associations between different usages of “bank” and words such as “river” “fisherman” or “teller,” which it learned during training. No doubt he would add that this doesn’t represent understanding in the human sense of the word. But is that true? ChatGPT is a neural network model that was originally developed to simulate how human brains might operate. It’s oversimplified, to be sure, and some details of its architecture are hard to imagine in a neuron and synapse brain, but it’s very conceivable that human understanding is based on something resembling synaptic weights and connections between neurons in complex networks that work by feed-forward algorithms, and that that’s where understanding “exists” in us.

“But,” Searle might protest, “you’ve described how ChatGPT produces accurate and appropriate words, but what about the feeling humans have when they know that they understand something?” I would argue that such a feeling, which normally exists only when someone asks us if we understand something, is not a constant companion, so to speak, of our listening to or producing language. And, such a feeling isn’t always accurate, e.g., “Q: Do you understand what a greenhouse gas is? A: Sure, greenhouse gases are produced by burning fossil fuels and cause global warming. Q. So what exactly is a greenhouse gas? A: You know, I’m not really sure.” In this case, understanding the meaning of a word or phrase refers to being able to use it appropriately in a conversation. To quote Wittgenstein, “For a large class of words, though not for all, in which we employ the word “meaning” it can be defined thus: the meaning of a word is its use in language.”(2) He points out that the meaning of a word cannot be divorced from its use in human interactions in what he calls “language

games.” According to Wittgenstein, “…the term ‘language-game’ is meant to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or of a form of life.”(3) Words, as they are used in conversations, don’t have static meanings. “Shoot” has a different meaning if we say it when we drop a bottle of ketchup on the floor, when we inform someone we’re going on a bird shoot this weekend, or when we sit in a movie theater and urge Dirty Harry to pull the trigger. ChatGPT, unlike Searle’s person in the Chinese Room who looks up answers in a book, “understands” when to use a word in the context of a conversation.

ChatGPT may be a simplified but plausible model of how the brain’s neural architecture produces thinking, but it may not be accurate. Many theories of how we understand word meaning rely on long-term memory storage, and ChatGPT doesn’t. But the Chinese Room is not a plausible model of human understanding, which, of course, is Searle’s point. It’s not a plausible model of how ChatGPT or other neural network models produce responses either.

References

1. Searle, J., 1980, ‘Minds, Brains, and Programs’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3: 417–57

2. Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical investigations. New York: Macmillan, PI 43e.

3. ibid, PI 23e.